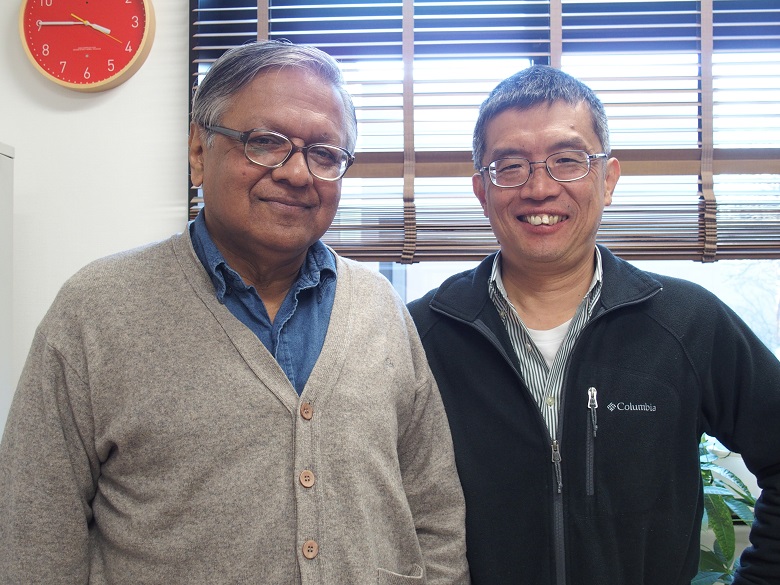

We are delighted to share the interview we had with our visiting faculties, Professor Emeritus Partha Sen and Professor Hodaka Morita, from Delhi School of Economics and The University of New South Wales, respectively. They were with us from November of 2015 until February 2016!! Please enjoy!

Growing up in 10 Janpath -- Soni Gandhi lives there now!

Q. Where were you born, and how did you spend your childhood days?

P: I was born in Delhi although we are Bengalis (my family came from what is now Bangladesh). So I spoke Bengali at home but Hindi outside the home. I spent my entire childhood in Delhi and left it to go abroad at the age of 26. Delhi in those days was very different from what it is now -- it had a small town atmosphere. My father was in a transferable job, so we used to live with my maternal grandparents in a very big government house.

There were 30 servants quarters (houses for servants). This was an old colonial house and is a very famous address today,

because a lady called Soni Gandhi lives there. She is the widow of a former prime minister and the leader of the main opposition party. Everyone in India knows 10 Janpath. Since the house had a big compound, my childhood friends were children from the servants quarters. It was really like living in a village in the centre of a city. I have very nice memories that one does not associate with present-day Delhi, which is an urban mess.

H: I was born in Tokyo, but when I was one year old, my father was transferred from Tokyo to Tsukumi in Kyushu -- he was a standard Japanese business man. My father was working for a cement company, and the cement company has a big plant in Tsukumi, so he was transferred there, and I had my first memory in Tsukumi. Until I was first year in primary school, I was in Kyushu, and then came back to Tokyo. Since then I was in Tokyo, so primary school, junior high, high school, university, Tokyo.

Kyushu dialect? Oh, yeah, I was bilingual at the kindie and first grade, both of my parents are Tokyo people, so at home I spoke the Tokyo Japanese, but at school, I was very fluent in the Kyushu dialect, I think.

Q. What were your dreams as a child, and your teenager days?

P: In my generation, we never dreamt. You ate, drank, and went to sleep. So things were like a rural setting, things were quite nice and placid … and boring. Boring because my parents never went to the movies, we never ate out, and there were cooks at home, and my mother was a very good cook, like everyone else’s mother! Nothing really by way of dreams, I couldn’t believe that I would grow up to become an economist one day, that came much later.

This was the time of the Vietnam war, and race riots in the U.S. I remember writing about these issues in the school magazine. The school authorities were not happy with what I wrote. I had definite views on the world, and therefore, I'm sure there were dreams associated with those.

H: I didn’t really have a strong dream, well of course, at three or four years old, starting from bus driver or train driver, those kind of things, and then when I was in primary school, like fourth, fifth grade, at some point I thought that I wanted to become a doctor, the physical doctor, but I don’t know if that was my parents’ dream or my dream, my parents kind of induced me to say it, but anyway, that dream disappeared relatively quickly. Since then, I didn’t really have a strong dream.

This was the time of the Vietnam War

P: Childhood, teenage … that was so long ago! Well, later teenage years, I should correct myself, I did have dreams, in a sense that I became kind of involved in some type of left-wing politics. This is the time of the Vietnam War, and this was the time of American race rides were happening and things like that, so I remember in high school I used to write for the high school magazine, and the authorities were not really happy with what I used to write. The Soviet invaded Czechoslovakia in ‘68, and I’ve written something on that, so yeah, later teenage years, I had definite views on the world, and therefore, I’m sure associated with that were dreams.

Q. How many languages do you speak? How did you learn them?

P: So I speak Hindi because that’s spoken in north India, Hindi is same as Urdu, which is spoken in Pakistan, except that the scripts are different. And Bengali, so I spoke Bengali with my parents, and it was limited to the kind of conversation that one has with one's parents. Later I met some students from Kolkata (some of them are Hodaka's friends) and then my Bengali improved. We had to learn English in school but I never spoke it with my friends, unlike my wife who went to a Christian missionary school where it was mandatory to speak English! So I often used to be very surprised that there’d be students in my class who would have come back from the U.S., who spoke perfect English, but their grammar was very bad. But with me, it was exactly the opposite, I spoke no English, but my written English and my understanding of it was much better.

I speak Nepali!!

H: I speak Japanese, English, and Nepali. When I was a Master’s student, I think at that time my dream was doing something interesting in Nepal. I like mountains, and I used to speak reasonable Nepali. But now, it is gone, although I remember some. But when I was doing MBA at Cornell, I’m pretty sure that I was the first MBA student at Cornell who took Nepali courses for two years! One thing I’m proud of was in Nepal, I was talking to a Nepali guy, and the guy thought that I was not a Japanese but a Nepalise person. But, I’m cheating a bit, because Nepal is a pretty multi-language country, and I think his mother language was not Nepalise, I think he was Tibetan or something.

Q. Why did you decide to take economics as your major?

H: That is a little bit passive, because when I was 18 years old, I decided to go for the economics department, and that was for no particularly strong reason. I thought law school was a risky strategy, so it was not because of economics, but because of availability and my ability to take exam. So when I was undergrad, I didn’t study economics very much, but when I wanted to do academia, so even though for me it didn’t really matter, but people who assess me looked at my transcript and said, “Oh, this guy did economics in undergraduate,” so that is the reason why I did economics. But it turned out that I’m relatively good at logical thinking. In that sense, economic theory turned out to be not a bad decision. And also I was able to apply my six years of experience working for a Japanese company in a unique way. Because many economists are very smart and clever, and those people do not really wonder like me. Starting from undergrad, they have determined to do economics, and right after undergrad, those people go to Ph.D. program, and when they turn twenty eight, they become Assistant Professor. Those people are very clever, very smart, but one thing they tend to lack is work experience, and that is what I have. I ended up doing OK, but that was just an accident rather than something I planned. OK, so I first have six years’ experience, and then did Ph.D. in economics, so by doing so, I should be able to do something unique compared to other people. Everything is more ex-post, happening rather than extensively planned.

P: Like I said, I had political views. I wasn't an activist. I thought economics is related to politics, and I opted for a BA degree in economics. I wanted to be an academic, a college teacher. To be a college teacher in those days was accepting a life of relative poverty. My father wanted me to join the civil service, but being Bengalis he treated academics with some respect (his father was a professor of mathematics). We come from a relatively poor family but with education. In Delhi (and Mumbai) unless you make a lot of money and have a big house, you are a failure in life.

So, I chose a life of relative poverty.

Q. When did you first consider becoming a researcher? What interested you the most?

H: After graduating undergraduate university in Japan, I joined the Nippon Steel Corporation for six years, and that was kind of a little low time of my life. And I didn’t find it really interesting. So I quit the company and I went to Cornell to do MBA. That time, I really studied hard. And probably that was the time I started to think that I might have some fit with academia. So it is late, I was 29 or 30 or something like that. Until then, I didn’t have much idea what I want to become.

P: Research is not something that I had given much thought to. But being a college lecturer in economics, I registered for a Ph.D. But I was not disciplined. I spent a lot of time sitting in coffee houses, gossiping and having political discussions. Over time, it was clear that if I wanted to finish a Ph.D., I would have to go abroad. You could not come back to India without finishing the Ph.D. because that would result in a loss of face. I went abroad, not because I was dying to. And went to the UK because I was still quite left wing and the U.S. was "reactionary".

I must say that this move really worked for me. And I consider myself very lucky.

Q. How and when did you meet each other?

P: In this very room, for your Christmas party!!

H: Yeah, but I had been hearing about Partha for many years, because now one of my best friends and co-author, colleague, a guy called Arghya Ghosh, was Partha’s student, and also when I was doing Ph.D., one of my closest friends amongst the Ph.D. students was Partha’s student.

P: They were in the same class, so I know them very well.

H: Arghya’s first paper is co-authored with you and published in Economica, which is a very good journal. So Delhi School of Economics, so one sort of a “golden path” of Indian economists, is to do undergraduate at the Presidency University, Kolkata, and do Master in Delhi School of Economics, and do Ph.D. in whatever places, so in case of Arghya Ghosh, it was Minnesota. Isn’t that right? That is one very standard path. So most Indian economists are friends with each other, and very friendly, tight community, they have.

Q: Do they go back to India, or do they mostly stay and pursue their careers?

P: They don’t go back. Now of course you have the second generation of Indians who are born in the U.S., grown up in the U.S., so therefore their ties with India is much weaker, but by and large, the academic economists have not gone back, they’ve stayed on.

H: But some of them eventually go back to India, for example, do Ph.D. in the U.S., find a job in the U.S. or Australia, and do academic job say 15 or 20 years, and then some people come back to India or not?

P: Not really.

H: Will they just be there, forever?

P: Kaushik Basu and I, we are of my generation, quite the exceptions. Some others have gone back, of course, but by and large they don’t.

Q. Were there any hurdles you have faced in your careers? If so, how did you overcome them?

P: Everyday! I did not choose the normal path. I had a job in the U.S., and I think would have got tenure (tenure is a tricky thing to predict).

H: So your first job was it in the U.S.?

P: Well, not my first job, but my substantive job was in the U.S., because my first job was in the UK, but in the UK at that time, you have one year contract to another, so I went to the U.S., hoping to be there for two years, but I ended up staying for five. But I always wanted to get back to India, mostly for personal reasons -- I wanted to bring up my children as Indians. When I did go back to India, my life was a real struggle, because the salaries were low, three children, the demands were high, my wife was not working, which made sense at that time because someone has to look after the children, so it was a real struggle.

Public transport was non-existent, unlike Tokyo, it would take me three to four hours for what is essentially a 20-minute bus ride, because the buses would be so crowded. So the quality of life in Delhi was really very bad. But I was relatively young, so you don’t seem to mind a lot of these things, and it was very good academically, so I have some of these students that Hodaka mentioned, and I was still at the age when I was like a friend or slightly older brother, so there were compensations, certainly, but in terms of quality of life, it was not very good, I think, physically.

Q: How did you overcome them?

P: The only way I could make my income equal to what I was spending was to go abroad and teach summer schools, or something like that. So that’s what I did. Then over time, Indian academic salaries have improved; so therefore today, I think you may not be rich but you have more than enough to live on. A colleague of mine (she was the wife of Hodaka's friend Tridip) would always insist on paying if we went to coffee shop, because she told me that since they had two (academic) salaries, they never manage to spend it all. This was very different from when I was her age.

I had four difficulties...

H: Hurdle in my life, meaning difficulties, right?! I had a lot of difficulties in my life. I started Ph.D. when I was thirty-three, which is, even in American standard, kind of pretty late. And in Japanese standard, it is very late. And English. So English is always one of my difficulties. Listening, speaking, writing, it’s difficult. And also, when I started Ph.D., as I said, my transcript said that I did economics in undergrad in Japan, but in fact I studied very little economics, and mathematics… my high school math was pretty good, but that’s it! Little mathematics, little economics, little English, well not little, but not really good English, and old, I was old, right?!

Especially the first year Ph.D., is a really tough thing, so the first year, I studied microeconomics, macroeconomics, and statistics and mathematics very very hard. And at the end of the first year, there’s the comprehensive examination, and if you fail it twice, then basically, you’re going to be kicked-out. It’s a big stress.

I thought, I have four difficulties, or maybe more than that, what should I do? I thought the answer was very obvious -- I should study!! I spent as much time as possible to study really hard, and also, in each class, if I’m behind today’s class, then I thought I won’t be able to catch up. If I don’t understand what the professor is talking about now, then that’s it, right? So I decided to ask whatever questions, even elementary questions, anything, if I didn’t understand then I asked. Whether or not people laughed, I didn’t care, I couldn’t care! But eventually, I realized that my classmates were waiting for me to ask questions. Because there were many questions which they did not understand but didn’t want to ask. People appreciate that, that guy is great, because he asks all kinds of questions. So right after each class, people went to lunch, but I cannot afford to go to lunch, I really needed to go to my Ph.D. student desk, and I summarized what I learned. I had to do it, because I had four difficulties, and the only way to overcome them, was to do this.

Q: You said before that you were married at that time, did that help in anyways?

H: Yes, probably so, since I didn’t have to make dinner or anything. And my wife is an optimistic person, so that helped me a lot also. If she were a nervous type, then both of us would become very nervous.

Q. What do you think is unique about yourself?

P: Never thought about it… I don’t think there’s anything unique. I’m very lazy, but that’s not unique. I don’t try hard, you know, people in my position would be utterly concerned, how come you’re not sending this paper to a good journal, but I’m not like that, so I don’t try and do, but I do what interests me. I’m lazy, so I think I get what I deserve, more or less, so I don’t know.

H: If I can interpret that as my strength and weakness, my weakness is I tend to be slow about thinking. But I recently think that that is not only weakness but also strength for me. I’m slow compared to other people. I need time to think about things and understand things. So when I present my seminar, for instance, presentation itself is okay, since I can spend a lot of time for preparation, but there’s a time for Q&A. And I try to anticipate possible questions, but if unanticipated questions are asked, I’m not good at answering them on the spot.

So, in terms of my strength, although I’m slow, I often come up with some ideas that others do not think. In some cases that is just a strange thought, but in other cases, that turns out to be something interesting. So that is probably how I make my living -- I tend to work with faster people, in terms of doing mathematics and economic modeling, and my task often is to think about things for a few weeks and (suggest) “maybe why don’t you do this,” and sometimes my co-author says, “ah, no, no,” so I say “okay,” and give it another week, and “what about this?” ”Ah, that’s interesting! I think nobody has done it before.”

Q. Do you have a cherished motto that you live by? Please share.

Q. Do you have a cherished motto that you live by? Please share.